Leopard

Seal on ice (Peter Lee)

An

orca has a look at the N.B. Palmer (Sasha Tozzi)

A

group of orcas (Sasha Tozzi)

The

dinoflagellate Protoperidinium. Some dinoflagellates can eat algae that are much

larger than themselves by attaching to the larger cell and sucking out its insides.

(Julie Rose)

The

ciliate Cymatocylis. Some ciliates and dinoflagellates will eat all of an algal

cell except its chloroplasts, which the grazer then uses to photosynthesize and

get energy for itself. (Julie Rose)

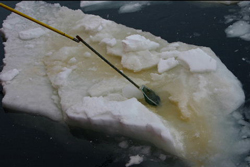

Sampling

algae growing under the sea ice.

Pteropod

Clione antarctica. (Jenny Dreyer)

Jack

DiTullio, chief scientist, anonymously nominated as "most amazing organism".

(Anonymous)

| CORSACS: Controls on Ross Sea Algal Community

Structure

2005: A Research Cruise to the Ross Sea to Study What Controls the

Phytoplankton DynamicsQuestions from High Tech

High School of North Bergen, NJ January 17, 2006

Dear Arctic

Exploration ScientistsWe, the biology students of High Tech High School

of North Bergen, NJ, recently had the opportunity to observe the phytoplankton

of the nearby Hackensack river, courtesy of the High Tech High School Riverkeepers. We

were wondering, if you can answer our question: "What is the most interesting

organism you have found on your expidition?" Thank you

Bio

classes and Ms. Lavlinskaia, a teacher ---------------------------------- Dear

Bio classes of High Tech and Ms. Lavlinskaia,

We received your email and thought

your question was wonderful. We are asking various members of the science party

for their opinions on which organisms were the most interesting and will get back

to you shortly (hopefully with pictures too). -Mak Saito ----------------------------- Here

are more answers: Hello - Rob Dunbar again. Even though nearly all

the scientists on this cruise are studying the very small plants that live here

in the Ross Sea, of course we also like the large and obvious animals we encounter.

Everyday we see Weddell seals and Adelie penguins. Most days we see a few Emperor

penguins and Leopard seals and Crabeater seals. We've also seen Minke whales and

a few Orcas (Killer Whales). Out of all the larger marine animals in the Ross

Sea, my favorite is the Southern Bottlenose Whale. While we haven't seen them

on this cruise yet, I have seen them about once every 5 years in the past. They

come into the Ross Sea to feed on fish in summer when the polynya is large. Why

do I like them? Well.....they are extremely rare and almost never observed by

man. They are large beaked whales and are white, like the Beluga whale of the

Arctic. Imagine a porpoise like Flipper. Then imagine it as 40 to 50 feet long

and white and shiny, like snow covered ice. Then imagine 15 of them travelling

together in a tight-knit family unit called a pod. If you want to learn more about

them, try searching on the web...... [NOTE - it was a Bottlenose Whale that

swam up the River Thames this past weekend (1/20-22). Unfortunately, it did not

survive the attempt to bring it back to the open ocean. See the following link

for online coverage: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/london/4635874.stm ] --------------------- Hello

- My name is Walker Smith, and I work at the College of William and Mary

Marine Institute in Williamsburg, VA.I have been working in the Antarctic for

22 years, and work on phytoplankton.Even though I work with microscopic organisms,

my favorite organisms down here are adelie penguins.Penguins occur throughout

the world, even in tropical waters, but they are most common in cooler waters.They

need certain locations in which to form nests, like other birds, as well as access

to the ocean to feed.So the numbers of adelie penguins are limited by both nesting

sites and foraging access. Adelie’s often look pretty silly on the

ice, as they waddle and slide across it to enter the water.Within the water, however,

they are incredibly agile and fantastic swimmers.Being sort of small (each one

weighs about 30 lbs.), they can change direction rapidly and swim very rapidly.To

exit the water, they simply jet out of the water and land on the ice.Landing,

however, can be a bit awkward, to say the least. Adelie’s in the Ross

Sea are really interesting, as they are one of the top members of the food web.They

eat mostly a special type of krill called crystal krill, as well as large amounts

of a small fish called Pleurogamma. They are obligate psychrophiles, meaning they

must have ice in which to exist and thrive. So if the ice were to melt, the Adelie

penguins would disappear. In the Antarctic peninsula, where it is warming very

fast (about 1ºF per decade, on average), Adelie’s are disappearing and

are being replaced by other penguins that do not use the ice.In the Ross Sea,

however, the situation is reversed; Adelie’s are increasing in numbers, perhaps

due to the increasing ice concentrations we find here.There are fossilized penguin

colonies, where scientists find old eggs and nests, and they can be dated accurately.

From them we know the temperatures thousand’s of years ago. One of

the largest penguin colonies in the world is located close to where we study at

a site called Cape Crozier. There are about 100,000 breeding pairs of Adelie penguins

there, and when they are actively feeding in the summer, they deplete their food

resources near the colony.So they have to forage, or gather food, up to 100 kms

(60 miles) from their nests.All of that time they are swimming in the ocean, and

can sometimes fall prey to their two major predators: orcas, or more importantly,

leopard seals.Leopard seals can grab a penguin and shake it when it is in its

teeth, and the carcass of the bird can come straight out of its skin and feathers!No

one said it was an easy life for a penguin. There are so many neat things

about these animals, and I am sure you can think of many questions you can’t

yet answer.For example, why don’t penguin feet freeze when they are on the

ice? How do they stay warm? How do they recognize their mate? How long do the

chicks stay with the parents? Or, how do they taste? [Hint: stick with chicken

tenders] If you can think of questions about penguins, let us know and we can

try to help you figure them out! --------------------- I love working

with algae, but I must admit that my favorite organism in the Antarctic is a little

bigger: the Killer whale (Latin name Orcinus orca). Killer whales were so named

because they were believed to attack human beings. However we now know this not

to be true. Killer whales are not actually whales but are the largest members

of the dolphin family (Family Delphinidae). They have a white abdomen as well

as a white patch behind the eye, and the rest of their body is black. Killer whales

in the Antarctic may have a brownish hue to their white patches because of diatoms.

They also have a very tall dorsal fin, which distinguishes them from other whales.

Male killer whales are larger than females, growing to 9 meters (30 feet) in length,

while females reach only 7 meters (23 feet). Killer whales are carnivores, feeding

on seals, fish, squid, penguins and even whales. In the Antarctic, killer whales

and leopard seals are the top organisms of the food chain. Killer whales can be

found in all of the world’s oceans, but live primarily in colder waters.

They travel in groups called “pods” that can consist of as many as 50

individuals. Most of the individuals are related and usually consist of males

and females, as well as calves and juveniles. Killer whales can remain under water

for up to 17 minutes and dive as deep as 260 meters (853 feet). -Aimee Neeley --------------------- My

favorite organisms in the Antarctic are microscopic, and I’m especially interested

in the kinds of microorganisms that eat algae. Scientists call these types of

organisms algal grazers, since they are feeding on plant-like microbes. My two

favorite groups of algal grazers are ciliates and dinoflagellates. Both of these

groups were named for their type of locomotion. Ciliates move around using structures

called cilia and dinoflagellates are named for the Greek word “dinos”,

which means ‘to whirl’. Dinoflagellates have two flagella, one that

propels them forward and one that causes them to spin as they move. As algal grazers,

these organisms can be really important in the food webs of aquatic ecosystems.

Ciliates and dinoflagellates can also do all kinds of neat things. Some dinoflagellates

can eat algae that are much larger than themselves by attaching to the larger

cell and sucking out its insides. Some ciliates and dinoflagellates will eat all

of an algal cell except its chloroplasts, which the grazer then uses to photosynthesize

and get energy for itself. I have included a picture of Protoperidinium, which

is a dinoflagellate, and Cymatocylis, which is a ciliate. -Julie Rose --------------------- Hey

there avid students of bio! Rob Dunbar here. I am a teacher and researcher at

Stanford University in California. Every summer I hire 3 to 4 high school students

to work in my lab - as science interns - so they can help us learn, and learn

themselves, about the Antarctic seas. My favorite organisms down here are

the ice algae - so named because they live inside the sea ice. These little plants

actually live in tiny channels filled with brine, within the solid sea ice. Sometimes

these brines are really salty - up to 3 times the saltiness of the ocean. And

these brines can be cold, as much as 10 to 20 degrees below zero centigrade. Yet

these little plants do just fine, and keep on growing, fixing carbon as long as

there is sunlight penetrating into the ice. In some areas of Antarctica, these

little ice algae are the base of the food chain. When you think that each year,

as you go from summer to winter to summer again the amount of sea ice that forms

and then melts is as large as all of North America, you can start to appreciate

how important these little guys must be....... Cheers,

Rob -------------------------- There

are many interesting phytoplankton organisms in Antarctica but I have also been

looking at what we find in zooplankton tows and they are equally interesting and

an important part of the Antarctic foodweb. One of my favorite organisms is the

pteropod, which is a mollusc. These animals are called sea butterflies because

they appear to fly through the water with appendages like wings. There are two

species we are finding here in the Ross Sea; Limacina helicina antarctica and

Clione antarctica. L. antarctica feeds on the phytoplankton has a shell similar

to a snail, and is black in color. In contrast, C. antarctica feeds on the Limacina,

does not have a shell, and is bright pink in color. Their graceful movements in

the water make them spectacular to watch as their wings move up and down. I never

grow tired of watching them and they are pretty amazing creatures. -Jenny

Dreyer

-------------------------- BACK |